Chapter 26: The Secret of Primitive Accumulation

Outline of Marx's Discussion:

Commentary

What makes capitalism a new kind of society has been the creation of

two new classes: a capitalist one made up of those who seek to organize most

people's lives around the work of producing commodities and another, a class

of workers, made up of those whose lives are subordinated to that organization.

The secret of this creation—hidden by pro-capitalist political

apologists in the telling of history—is that the emerging class of capitalists

imposed this social order with brutality and violence, forcibly serparating

people from their means of livelihood and destroying their ways of life.

Those means included: privately owned tools, formal and informal land tenure and

commons, such as pastures, fishing waters, forests and often language and culture

to which everyone in a community had acess. Although this forcible separation

created a situation where the reality (and threat) of destitution and starvation

would largely replace the lash as a coercive instrument of control, violence

continued to provide capitalists with a supplementary weapon for keeping people

subordinated, right down to the present. This is true whether the violence has been

wielded by corporate goons, paramilitary thugs or by government police and military.

Marx both critiques political economy by showing it to be at once apologetic

and false and gives an overview of the actual processes through which

capitalism emerged as a new kind of social order—an outline of the history

he examines more thoroughly in the subsequent chapters.(3)

His analysis temporarily ignores the central subjects of political economy

—the interactions of "money and commodities"—to focus on the social

social conflicts that shaped the new world in which those things came to figure

so centrally. The violence that capitalists required to impose their order

reveals the depth of resistance. The agents of this new order, the "knights of

industry", exploited every opportunity to achieve power, to subordinate

the exploited classes of the old order in a new way and to usurp the power of

the feudal lords, the "knights of the sword." Here the nascent

capitalist class is portrayed as using "base" means, of "making use of

events in which they played no part whatsoever" and of using various

"revolutions"as "levers."

The Myths of Political Economy

Myths about the class structure of capitalism have served to justify its historical

origins and on-going class disparities. The central myth, still promulgated today,

is a morality tale that portrays capitalists as obtaining their wealth by frugally

saving and investing. It suggests that everyone has always been able to become

a capitalist by the same means, and those who do not, have no one

to blame but themselves.

In 19th Century English literature, this myth was already the object of ridicule

far more ascerbic than that of Marx's. For example, in Charles Dickens's

(1812–70) 1854 novel Hard Times, which narrates

the lives and tragedies of several people in a fictional Manchester-style,

manufacturing city called Coketown, we find many passages where various persons

are repeating this myth. Examples include the self-praising speeches of Mr. Josiah

Bounderby—the novel's central capitalist—constantly bragging (falsely

it turns out) about how he raised himself out of the mud to his present august

position as mill owner and banker. (4)

More concise, however, is a pretty exchange

between Bounderby's ex-housekeeper Mrs. Sparsit and Bitzer, his light

porter, general spy and informer at the bank, in which the

repetition of the myth reveals both a distain for those irrational

creatures (the workers) who put human relationships before personal profit

and a self-delusion about the origins of wealth. Both, of course, are merely repeating

the self-justifying truisms of Bounderby in an almost ritual, and mutually

reinforcing, manner. (5)

The effect is both comic and appalling.

This, again, was among the fictions of Coketown.

Any capitalist there, who had made sixty thousand pounds out of sixpence,

always professed to wonder why the sixty thousand nearest Hands didn't

each make sixty thousand pounds out of sixpence, and more or less reproached

them every one for not accomplishing the little feat. What I did

you can do. Why don't you go and do it?

"As to their wanting recreations, ma'am," said

Bitzer, "it's stuff and nonsense. I don't want recreations.

I never did, and I never shall; I don't like 'em. As to their combining

together; there are many of them, I have no doubt, that by watching and

informing upon one another could earn a trifle now and then, whether in

money or good will, and improve their livelihood. Then, why don't

they improve it, ma'am! It's the first consideration of a rational

creature, and it's what they pretend to want."

"Pretend indeed!" said Mrs. Sparsit.

"I am sure we are constantly hearing, ma'am,

till it becomes quite nauseous, concerning their wives and families," said

Bitzer. "Why look at me, ma'am! I don't want a wife and family.

Why should they?"

"Because they are improvident," said Mrs.

Sparsit.

"Yes, ma'am," returned Bitzer, "that's where

it is. If they were more provident and less perverse, ma'am, what

would they do? They would say, 'While my hat covers my family,' or

'while my bonnet covers my family,'—as the case might be, ma'am—'I have

only one to feed and that's the person I most like to feed.'"

"To be sure," assented Mrs. Sparsit, eating

a muffin.

"Thank you, ma'am," said Bitzer, knuckling

his forehead again, in return for the favour of Mrs. Sparsit's improving

conversation. "Would you wish a little more hot water, ma'am, or

is there anything else that I could fetch you?"

(from Charles Dickens, Hard Times, Book the second: Reaping,

Chapter 1: The Effects in the Bank.)

|

A subtler, but even more biting indictment of the myth

of the self-made man, is contained in Charlotte Brontë's first novel

The Professor which was written in 1846 but not published until

after her death in 1857. The protagonist, a young man who becomes a school

teacher, rather than a capitalist, only achieves success by fully participating

in a dog-eat-dog world fully shaped by the laissez-faire,

competitive capitalism of the 19th Century. The novel portrays the

necessary combination of aggressiveness and defensiveness required for

survival, as well as the ultimate loneliness and isolation of even the

most successful competitors for status and love. It is an amazingly

modern treatment of what Marx in his 1844 Manuscripts and social

critics in the 20th Century call the alienation of capitalist society.

The pressures to which the young professor succumbs and the behaviors that he

adopts continue to be depressingly widespread in contemporary academia where

academics are pitted against each other in an endless struggle for publication,

research funds and promotion.

In American literature and popular culture, this myth has taken many forms,

including the novels for young adults of Horatio Alger (1832–99). With the rise

of the modern corporation with its many-leveled wage and salary hierarchy, the

myth has taken the form of stories of energetic individuals who work hard and

scheme their way up that hierarchy, perhaps even to the top. From Horatio Alger’s

young men to Michael J. Fox in The Secret of My Success (1987) or

Melanie Griffith in Working Girl (1988), the myth has changed little.

It has, however, also been repeatedly critiqued, in novels such as Sinclair

Lewis’s Babbitt (1922) or poems such as Edwin Robertson’s “Richard Cory”

(1897), made famous in Simon and Garfunkel’s

musical interpretation (1966).

(6) I return to these critiques in my

commentary on Chapter 7.

Controversy: Was Marx an "Historical Materialist"?

Declining to take on the history of capital everywhere, Marx announces

that he will take the example of England as the "classic" case. And

indeed throughout Capital most of Marx's examples are drawn from

British history although from time to time, including this section on

primitive accumulation, he brings in the experiences in other countries.

However, since Capital was published in 1867, there are many who have

tried to convert Marx's analysis of the rise of capitalism into a general theory

of history, i.e., historical materialism. Engels's efforts in this

direction built on a few generalizations that he and Marx had made in their early

joint works The German Ideology (c.1846) and The Communist Manifesto

(1848). In the former, they insisted on the material foundations of

human life in the genesis of ideology. In the latter, aimed at differentiating

their communist movement from a variety of socialist efforts,

they famously wrote: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history

of class struggles." A decade later, in his brief preface to his Contribution

to the Critique of Political Economy (1850) Marx wrote:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite

relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production

appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of

production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic

structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political

superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness.

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social,

political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines

their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come

into conflict with the existing relations of production or—this merely expresses

the same thing in legal terms—with the property relations within the framework

of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive

forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social

revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the

transformation of the whole immense superstructure.(7)

Given the generic character of this passage, characterizing human history in

general, it is easy enough to see why some would see it as a first step toward

a general theory of human history. Engels, but not Marx, went on to attempt the

elaboration of such a general theory in writings such as Anti-Dühring

(1878) and The Dialectics of Nature (1883), where he pushed beyond

a general theory of history, to sketch a virtual cosmology—a dialectical

materialism encompassing all of nature as well as human history, a cosmology

in which historical materialism constituted a subset of a broader vision.

These works became essential references for official Soviet ideology, referred

to in shorthand as histomat and diamat. At their nadir, during

Stalin’s regime, both were reduced to a virtual catechism to which all Soviet

intellectuals were forced to adhere. They were also used to justify—when it

suited Soviet interests—demands that members of the Soviet-organized Third

International in regions of the Global South support the development of capitalism

against so-called “feudal forces.” In the wake of Stalin’s death in 1953 and of

the Soviet crushing of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, the theory was refurbished

as an elaborate structural model by Althusser and his collaborators. The ongoing

appeal of one version of historical materialism or another is evident in the

continuing publication of the academic journal Historical Materialism

(1997–), its conferences and its book series.

Unfortunately for those attached to the idea of a general theory of history, Marx

wrote his own commentary on this kind of interpretation of his work. One author

to whom Marx took exception was Nicolai K. Mikhailovski (1842–1904) who had used

Marx’s analysis of primitive accumulation to argue the historical necessity for

all countries, including Russia, to pass through the stage of capitalism. Yes,

the czar should be overthrown, but that overthrow must be followed by accelerating

capitalist industrialization of the country. This was a highly political issue in

Russia in the 1870s and remained so right through the Russian Revolution when the

Bolsheviks seized power and pursued precisely such a policy. Others, such as the

populists, recognized no such inevitability, argued and organized for a revolution

of workers and peasants that would undercut the beginnings of capitalism in

Russia and permit a direct passage from the traditional village mir

(a communal form of organization) to communism. In the process of rejecting

Mikhailovski's interpretation, Marx refuses the conversion of his theory into

"historical materialism":

It is absolutely necessary for him to metamorphose my historical sketch of the

genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into a historico-philosophical theory of

general development, imposed by fate for all peoples, whatever the historical

circumstances in which they are placed.(8)

Elsewhere in the same letter, to illustrate his objection to applying his analysis

willy-nilly, Marx points out how the expropriation of peasants in ancient Rome

led not to wage labor but to slavery.

Four years later, in a letter to Vera Zasulich (1849-1919), he again

rejected the generalization of his theory and insisted on the open-ended

possibilities of the Russian village mir as the basis of

a new society:

The historical inevitability of this process [the genesis of

capitalist production] is, expressly limited to the countries

of Western Europe . . . Hence, the analysis presented Capital

does not adduce reasons either for or against the viability of the rural

commune, but a special study which I have made of it and the material which I drew

from original sources, has convinced me that this commune is the fulcrum of the

social regeneration of Russia . . . (9)

He hoped, we now know, vainly, that revolution might give the mir a chance to

become the point of departure for the growth of an alternative, more attractive

culture and civilization. (10)

From these notes and from the treatment in Capital I draw

two conclusions: first, this section on primitive accumulation shows the conditions

and processes through which capitalism emerged and which it must maintain to

reproduce its social order. People must be separated from alternative means of

livelihood and driven into the labor market, where they can gain their bread only

by working for business. (11)

Second, it is a mistake to see this analysis as a linear

stages theory that says all peoples have to pass through these processes.

Even today, when it can be argued that all countries have long been caught up in

the capitalist web and their workers fitted into its net of exploitation, there

is nothing in Marx that argues each subordinated group must progress through

predetermined stages of development before they can fight to be free of capitalism.

In a world organized around an extremely complex multinational division of labor,

it makes no sense to interpret the call for a “universal development of productive

forces” as a call for universal industrialization. Marx shows us how capitalist

development has always involved underdevelopment, both as a process and as a

strategy. The development of capitalism is not only based on the underdevelopment

and impoverishment of all other modes of life but in the process, it generates a

poverty it can never abolish because it provides an ongoing threat that not being

directly exploited by capitalism can be worse than being exploited by it.

(12) The

division of labor, a corresponding income hierarchy and the promise of upward

mobility have provided capitalists with carrots to induce acceptance of its rules

of the game, but also with the sticks of unemployment and poverty to club people

into line when the carrot does not provide sufficient motivation.

Extensions: Capitalism Can Not Eliminate the Alternatives

As he argues here, and again in Chapter 25 on accumulation, capitalist development

never means giving everyone a living wage in exchange for work. On the contrary,

many, perhaps most (on a world scale) of those whose previous ways of life are

progressively destroyed are doomed to remain unwaged and poor.

This is one reason why so many people have resisted and fought to preserve their

independence as communities and their uniqueness as cultures. In the United States,

as in other so-called developed capitalist countries, most people have

lost that struggle and been swept into the world of factories, offices, ghettos and

suburbs. Some have preserved unique cultural attributes by forming rural or urban

communities. We have the Amish in the countryside, Native Americans on reservations,

and ethnic communities in cities. Others, from time to time, have broken away to

form intentional communities that escape, to some degree, subordination to wage

labor. But most people have been integrated into the waged/unwaged hierarchies

of capitalist society. In the Global South, where factories have been fewer and

capitalist development has concentrated its poverty, a higher

percentage of people have had better luck in preserving some land, some

control over their means of production and more of their traditional culture.

They are not outside of capitalism, they too are exploited, as we will see,

in a variety of ways, yet they still have some space that supports their

ongoing struggle for autonomy. In Capital, Marx does not talk

much about these situations because his historical examples are mostly drawn from

the British Isles where very little of pre-capitalist social forms and culture

survived.(13)

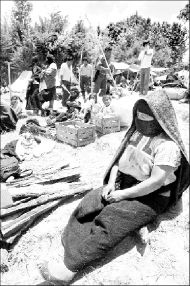

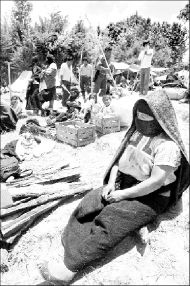

One place where access to land and community cohesion have made possible

resistance to total subsumption to capitalism and a certain degree of autonomy is

Mexico. In the early 1990s, in the run-up to the passage of the North American

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Mexican government pushed through a consitutional

amendment aimed at undercutting one of the few fruits of the Mexican Revolution

(1910-20) won by peasants and the indigenous: the collective ownership of land in

the form of ejidos where the land belonged to communities and not

to individuals and could not be bought and sold. While not organized like

the Russian mir, the ejidos nevertheless provided

the material foundations for peasant, especially indigneous, communities to survive and

preserve elements of their languages, music, dress and self-organization

quite different from the institutions of the centralized Mexican

state. Thus, they have formed unwanted rigidities to Mexican and

American business with an interest in expanding their investments

and tapping more people as cheap labor.

While the amendment of the Mexican constitution pleased business, indigenous

communities saw it as a death knell foretelling widespread ethnic genocide.

As a result in the southern state of Chiapas the indigenous members of many

communities united to form, equip and launch a rebellion against such a destiny.

These are the Zapatistas, self-named after one of the heroes of the Mexican

Revolution, Emiliano Zapata (1879-1919), a peasant from the state of Morelos who

became leader of the Liberation Army of the South.

On January 1, 1994, the same day NAFTA went into effect, fighters of the

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN, or Zapatista Army of

National Liberation) poured

out of the jungles and forests and seized six cities in Chiapas. As they did so

they explained their rebellion as a last ditch defense against their

extermination as peoples and demanded official recognition of their rights to

preserve and evolve, in their own ways, their traditional forms of social

organization. The Mexican government counterattacked with troops but was soon

forced into negotiations by widespread protests all over Mexico and around the

world. Those protests were sparked by the ability of the Zapatistas, especially

their main early spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos, to clearly articulate not

only NAFTA's threat to their communities and their demands for autonomy, but also

a more general critique of neoliberalism that resonated around the world so

much so as even to inspire foreign musicians, such as the band Rage Against the

Machine to celebrate their rebellion in the song

"People of the Sun."

(14) Outflanked

and defeated repeatedly in the subsequent political struggle, the state attacked

again in early 1995 and was again forced to back off.

Over the last two decades, the conflict has continued and so far, despite the

consitutional amendment permitting communities to be privatized, broken up, sold

off and dispersed, the indigneous of the Zapatista movement have been successful

in resisting such pressures. Indeed, they have continued to reorganize themselves

in more and more explicitly anti-capitalist ways and carried those efforts to the

rest of grassroots Mexico seeking ways of building a nationwide, anti-capitalist

movement. (15)

They continue to resist the final enclosure of the Mexican countryside

and the completion of the kinds of processes described by Marx in these chapters.

Because many pre-capitalist forms in Britain were also exploitative, such as

the rural world of tenants dominated by a landed aristocracy,

Marx had no nostalgia for them. In many areas of the rest of the world, however,

those cultures which predated capitalism were either not exploitative, or the

people had spheres of autonomy filled with their own traditions, skills

and rituals, as in Mexico where strong elements of precolumbian, mesoamerican

culture have survived and evolved. (16)

Where capitalism has succeeded in destroying such

cultures the world has suffered an absolute loss of cultural diversity

and human meaning with little to take their place other than the alienated

world of capitalist poverty. Where capitalism has failed to impose its own

rules of the game because of peoples' resistance, the conflict continues.

Late in his life, Marx not only studied the peasant mir in Russia but also

delved into anthropological works on so-called primitive cultures, looking, his

notebooks suggest, for further possibilities of avoiding the evils of capitalism

through the further development of autonomous cultural practices.

(17)

Today, we can look around the world, to some degree here in the U.S.

and in the other "developed" capitalist countries, but to a larger degree

in the Global South and see the wide variety of distinct ways of life which

have been preserved (with change of course), or invented, that still offer a

diverse array of alternatives to the dominant culture of capitalism.

Whether these alternatives are judged satisfying or seen as points of

departure, they show something extremely important: capital has never

been able to shape the world entirely according to its own rules.

Beyond the survival of pre-capitalist cultural practices, people have also

repeatedly created new kinds of social relationships that are incompatible

with the capitalist rules of the game and in the process, have posed new

alternatives to it. In his theoretical chapters, Marx shows capitalism really has

no creativity at all, but lives by absorbing and harnessing the creativity of

those it dominates. The realization of this constant failure of capital to bend

all people during all their lives to its demands alerts us to the essential

source of potential change: those alternatives preserved and created through struggle.

With these notes of warning about too simplistic an adoption of

Marx's analysis as being universally valid in its details, and

even more so as being a prescription for a painful but necessary historical passage,

we can proceed to examine the elements of this original accumulation

which Marx selected for detailed treatment

RECOMMENDED FURTHER READING

On the issue of the myths of political economy, there are three

types of literature. The first, is that which portrays the myths

and contributes to their promulgation. In the United States, the best known

of this sort are the stories of Horatio Algers such as

Ragged Dick

(1867) and

Struggling Upward (1890) which have been reprinted

together in a Penguin American Library Edition (1985). The second, which

I have cited and

quoted in my commentary, critiques and sometimes ridicules the myths.

This includes both literary treatments such as Dickens' Hard Times

(1842)

or Brontë's The Professor (1846) and the more analytical

treatments

of Marx's 1844 Manuscripts or such contemporary treatments as

David Riesman's The Lonely Crowd, 1953 or Erich Fromm's The

Revolution of Hope: Toward a Humanized Technology, 1968. The third

type of material is that of professional historians which describe the

actual rise of capitalism in all its brutality and ugliness. Such material is not as vast as

the reality but reliable accounts are available for many areas of the world,

from Britain and other areas of early capitalist development, from the

Global South where capitalism extended its rule via colonialism, and later,

after World War II, continued to dominate in various forms of neocolonialism.

For the rise of the English working class, as seen from the bottom up,

see the following three supurb works: Edward Thompson, The Making of the

English Working Class, New York: Vintage, 1963, Christopher Hill,

The World Turned Upside Down, New York: Penguin, 1972 and Peter Linebaugh,

The London Hanged, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

On the issue of whether Marx was an "historical materialist",

you can read both those who claim that he was and his own words arguing

that he was not. The former was the official line of the Soviet

Communist Party and its derivitives as well as various other more or

less "orthodox" Marxist tendencies which have seen him both as the

philsopher of "dialectical

materialism" and as the social scientist of "historical materialism.

The Soviets published a selection of writings by Marx, Engels and Lenin

that they felt contributed to the definition and development of historical

materialism: K. Marx, F. Engels and V. Lenin, On Historical Materialism:

A Collection, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972. A typical contemporary

orthodox treatment is Maurice Cornfoth, Historical Materialism, New

York:

International Publishers, 1971. A more sophisticated Althusserian

formulation is given by Étienne Balibar in his essay "The Basic

Concepts of Historical Materialism" included in Louis Althusser and

Étienne

Balibar, Reading Capital, London: New Left Books, 1970.

A critique

of the Althusserian version of historical materialism is given by Edward

Thompson in his The Poverty of Theory and Other Essays, New York:

Monthly

Review Press, 1978. A more recent evaluation is Stanley Aronowitz,

The Crisis in Historical Materialism: Class, Politics and Culture in

Marxist Theory, New York: Praeger, 1981.

For a more detailed discussion of Marx's work and thoughts on

19th Century Russia, see Teodor Shanin (ed) Late Marx and the Russian

Road,

New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983 which includes the letters to Zasulich.

On the issue of existing alternatives to capitalism, living within the

interstices of capitalist domination, there are two kinds of material.

First is that of anthropology which has been devoted to studying such

cultural

survivals on the margins of the industrial countries and throughout the

largely non-industrialized ones of the Global South. The literature

here is obviously too vast too cite, but contemporary struggles of such

peoples to survive and evolve are chronicled and supported in the journal

Cultural Survival Quarterly. Second is that of the history of

"working

class culture" or of popular counter-culture which has been generated and

reproduced within the struggle against capitalist domination. This

includes not only the struggles of daily life and such mass movements of

as those of the 1960s, but also the accounts of recurrent efforts to

elaborate

intentional "utopian" communities in autonomous spaces carved out of the

larger capitalist society. Here again the literature is enormous.

CONCEPTS FOR REVIEW

primitive accumulation

frugal elite

lazy rascals

force

historical materialism

working class

capitalist class

development and poverty

|

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

(An * means that one possible answer to that question can be found at the

end of the study guide.)

*1. What is the idyllic myth of the origins of capitalism, according

to Marx? What is his critique of that myth?

2. What are the two senses in which workers are freed during the period

of the emergence of capitalism? What two transformations are involved?

3. Who did the industrial capitalists come to replace in society?

4. Over what period does Marx consider capitalism to have emerged?

5. In footnote #1 Marx notes a case where workers who had once been driven

into the cities came to be once more driven into the countryside.

How is land reform like this process he describes?

6. What is the role of force Marx sees in the emergence of capitalism?

*7. What can we deduce about peoples' response to primitive accumulation

from capital's need to use violence to impose its new kind of civilization?

8. "Only in England, which we therefore take as our example, has it

(primitive accumulation) the classic form." England is for Marx his

most steady point of reference and source of examples throughout

Capital.

Do you think this means that he sees in the history of the rise of

capitalism

in England an inevitable series of steps through which all societies pass?

As an intellectual exercise, collect all the quotes you can to buttress

such a position.

*9. How did Marx respond to Mikhailovski's application of the analysis

in Capital to the case of Russia? Does he embrace or reject the

interpretation of his theory as a general "historical-philosophical

theory of universal development"?

10. Discuss the relationship of Marx's analysis in this chapter with

the structure of presentation of all of Part VIII in this volume.

11. From the reading of this chapter, what can you say about Marx's

concept of the working class? of the capitalist class? of class?

If not everyone has been drafted into the waged working class, through

what other ways can you think of have people been forced to work for capital.

*12. Discuss the issue of cultural creation and destruction in the rise

of capitalism. Give some examples of cultures which were mostly,

or entirely destroyed. Was this destruction a one-time phenomenon

of primitive accumulation or has it been an ongoing process?

Footnotes

1 Capital, Vol. 1., p. 874.

2 Ibid., p. 875.

3 This opening makes clear why the subtitle of

Volume I of Capital is "A Critique of Political Economy." His critique

does not provide an alternative political economy or economic theory of capitalism,

but rather an analysis designed to inform struggles to overthrow it.

4 Dickens's character, Mr. Josiah Bounderby,

has found a real-life incarnation in Donald Trump; the parallels between their

incessant, narcissistic bragging and their lies about the sources of their wealth

are striking.

5 Here too are parallels with the sycophants

with which Trump surrounds himself.

6 Edwin Arlington Robinson, Selected

Poems, New York: Penguin Classics, 1997.

7 MECW, vol. 29, p. 263.

8 Marx to Otechestvenniye Zapiski,

November 1877, MECW, vol. 24, p. 200.

9 Marx to Vera Zasulich, March 8, 1881, MECW,

vol. 24, pp. 370-371. Also available in the same volume are three drafts

of the letter. See pp. 346-369.

10 These letters have played a role in

efforts to show how Marx's later work escaped what seemed to be its early limitations.

See Teodor Shanin, Late Marx and the Russian Road: Marx and the Peripheries

of Capitalism, New York Monthly Review Press, 1983 and Kevin Anderson,

Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity and Non-Western Societies,

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

11 In recent years, a debate arose about

whether Marx's analysis of primitive accumulation is only applicable to the period

of the rise of capitalism or also explains continuing processes of enclosure,

dispossession and the imposition of markets in contemporary capitalism. See the

articles collected in the second issue of the online journal The Commoner,

September 2001.

12 This point was apparently made so frequently

by the English economist Joan Robinson that the statement “The only thing worse

than being exploited by capitalism is not being exploited by capitalism” has been

repeatedly attributed to her. See her An Essay on Marxist Economics,

London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd rev. edn., 1967.

13 Fortunately, a bit more has survived in

England's first colonies, Wales (1282), Ireland (1603) and Scotland (1707),

especially, for those of us who appreciate things Celtic, their traditional

language, music and folklore. Capitalists, of course, try to co-opt/instrumentalize

all such survivals—just as they do with wholly new artistic and musical creations

—by turning them into profitable commodities and spectacles. Thus, folk and

even protest music often wind up being sold for a profit. Of course, in the

process capitalist commodification often becomes a vehicle for the widespread

circulation of anti-capitalist messages and struggle. In the place of wandering

troubadours such as Joe Hill (1879–1915) and Woody Guthrie (1912–67), who

inspired workers' struggles as they moved from place to place, came LP recordings

of Pete Seeger (1919–2014) spreading their songs across the USA, and Bob Dylan

(1941–) inspiring the cultural revolution of the 1960s through LPs, tapes and

televised performances. Today, with peer-to-peer digital sharing, YouTube and

various social media, capitalist commodification has become more difficult and

the circulation of anti-capitalist art and music more widespread than ever before.

See Brett Caraway, "Survey of File-Sharing Culture", International Journal of

Communication, no. 6, 2012, pp. 564-584.

14 “People of the Sun” got Rage Against the

Machine banned by the Mexican government until 1999 when they were finally able

to stage a concert in Mexico City. See their video The Battle of Mexico City

(2001). The Zapatistas and their supporters have made extensive use of social

media, beginning with email and webpages, to circulate information about their

struggles and to coordinate resistance to government repression. See H. Cleaver,

“The Zapatistas and the Electronic Circulation of Struggle” (1995), in John

Holloway and Eloina Peláez (eds.), Zapatista! Reinventing Revolution in

Mexico, Sterling, VA: Pluto Press, 1998, pp. 81–103.

15 This was the objective of

“The Other

Campaign” launched in 2005 as an alternative to presidential elections in Mexico.

Having won a certain freedom to travel by dint of continuous struggle, a group

of Zapatista spokespeople carried their message and questions about democratic

alternatives to Mexico’s formal electoral system throughout Mexico.

16 See Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, Mexico

Profundo: Reclaiming a Civilization, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996.

17 See Lawrence Krader (ed.), The

Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx: Studies of Morgan, Phear, Maine, Lubbock,

Amsterdam: Van Gorcum & Co., 1972 and Anderson, Marx at the Margins.