Popular Culture & Class Struggle

I hate a song that makes you think that you are not any good.

I hate a song that makes you think that you're just born to lose,

bound to lose, no good to anybody, no good for nothing,

because you're either too old or too young or too fat or too thin

or too ugly or too this or too that . . .

Songs that run you down or songs that poke fun at you

on account of your bad luck or your hard travellin'.

I'm out to fight those kinds of songs

to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood.

I'm out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world,

and that if it has hit you pretty hard, and knocked you for a dozen loops,

no matter how hard it’s run you down and rolled over you,

no matter what colour, what size you are, how you are built,

I'm out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself

and in your work. And the songs that I sing are made up

for the most part by all sorts of folks just about like you.

Woody Guthrie

What constitutes so-called "popular" or "low brow" culture, i.e.,

those aspects of culture which occupy the general population, as

opposed to “high brow” culture (classical music, avant garde

art, theater, opera) which is generally viewed as being produced

by and for a “cultural elite,” changes over time but has

often been defined to include a wide variety of activities and

media, from daily life activities (patterns of family interactions

to television and schooling) to special events (carnivals, comic

books), film (grade B, drive-in), theater (street) and literature

(romance novels, westerns, science fiction). While these two terms:

popular culture and high brow culture have not generally been given

class specific definitions, there has been a tendency among Marxist

critics to understand popular culture in terms of the amusements and

life styles of the working class and high brow culture in terms of

those of the wealthier leisure classes, e.g., the bourgeoisie in

capitalism.

Historically, Marxists have generally distinguished between those

aspects of popular culture which have been produced by working people

themselves, e.g., folk art, tales or music, and those aspects which

have been produced for them, e.g., commercial television, advertising,

arcade video games, film and music. This distinction is usually

associated with a valorization of the former — as being authentic

expressions of mass creativity — and deprecation of the former —

as being mechanisms of cultural pacification and domination. Indeed,

the Marxist literature dealing with culture has had two distinct strands:

one rediscovering and celebrating manifestations of “authentic”

grassroots culture, the other elaborating a detailed critique of the

mechanisms of cultural domination via consumerism and the society of

the spectacle.

Unfortunately, these two strands of work have largely stood outside

each other, whereas, what we need is a recognition and analysis of

how these two forces interact to produce the cultural world that

surrounds us. For while it is true that some working class intelligences

and imaginations have been harnessed to the task of crafting manipulative

cultural experiences, be they passivity inculcating spectacles or order

inducing lessons in consumption, work discipline or allegiance to

authority, it is no less true that much of this work of domination

involves desperate attempts to deflect, redirect or otherwise nullify

dangerously antagonistic cultural innovations created by rebellious

spirits unharnessed by any of the existing capitalist mechanisms. As

a result, a great deal of popular culture of all kinds contains

conflicting currents of critical revolt against the status quo as

well as attempts to neutralize and tame such currents.

One of the spheres of culture in which these conflicts are most

clearly played out is popular music. From traditional folk and

country music through rhythm & blues to modern jazz and all the

permutations of rock & roll, we can find these conflicts shaping

the lyrics, musical styles and evolution of popular music. At the

one extreme are overt “protest songs”, such as those so popular

during the cycle of struggles of the late 1960s in which civil rights

and anti-war militants wrote, sang and played music aimed to mobilize

social movements against existing institutions and policies. At the

other extreme is such commercialized, mechanical music as disco or Muzak

designed purely for manipulation and profits. In between, and even to

some extent within these extremes, we find an endless variety of mixtures

of intentions, roles and effects. Shaping these mixtures are, on the one

hand, the creativity of song writers and musicians reacting to, or with,

and often against, the world that surrounds them; a creativity that

restlessly and repeatedly breaks out of old forms and styles and thought

patterns to craft new reactions and interventions. On the other hand

are the forces of capitalist commercialization and its tools of

ideological warfare.

Educated in a ruling class culture, Marx illustrated and buttressed

his arguments in Capital with a wide variety of pithy quotes from

classical authors, from Aristotle to Goethe — which helped give

him a reputation for being extremely erudite as well as extremely

radical. Understood within their context, these quotes often not

only illuminate Marx’s analysis but also add considerable humor

to his presentation. When it comes to reading Capital, however,

especially when reading it at the beginning of the 21st Century as

opposed to situating it in the 19th Century, I find it as amusing

to draw on the various moments of critique in contemporary popular

culture, especially in music, as to search out modern counterparts

to Marx’s classical references. For this reason I have included

in this study guide, and may sometimes play in class, a wide variety

of more or less contemporary folk and rock songs which provide both

an auditory illumination of the text and demonstrations of how the

relationships that Marx treated are, unfortunately, still with us today.

In the same spirit I have included a variety of graphic art — political

cartoons, comic strips, graffiti, advertisements and so on — which also

reflect the continuing pertinence of Marx’s analysis in our present.

These various moments of popular culture are presented without commentary

in this study guide so that you can simply enjoy them in their immediacy.

I will provide more or less detailed commentary on various of them in

class lectures. Again and again, in many different forms, styles and

media, the illustrations included can easily be seen, and understood,

as manifestations of a pervasive resentment of and rebellion against

the most fundamental social mechanism of capitalist domination: the

imposition of work.

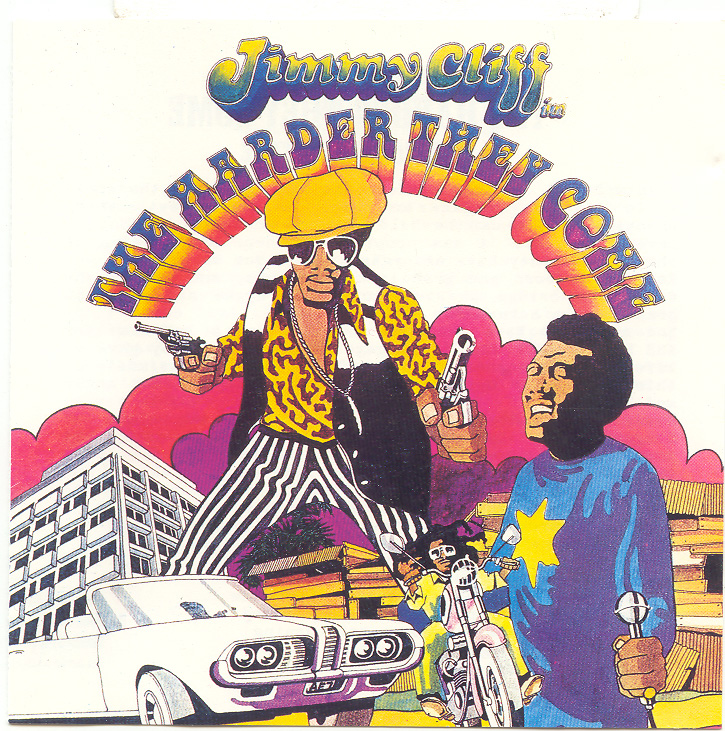

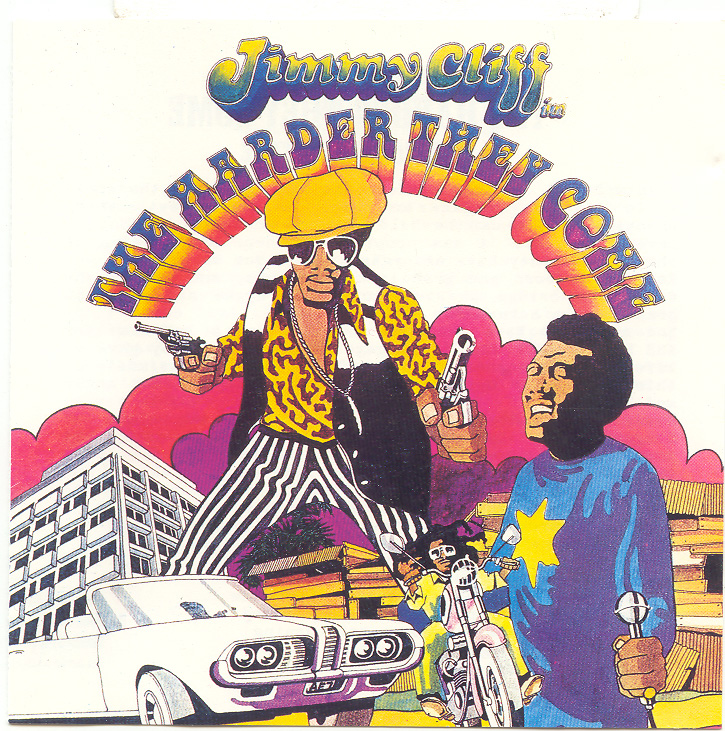

The first of these illuminations are out and out protest songs: Pink

Floyd’s "The Happiest Days of Our Lives" and “Another Brick in

the Wall” from their famous concept

album The Wall which protests the deadening

effects of school and teachers on students’ creativity and freedom,

and two songs from Jimmy Cliff’s film The Harder They Come

which express the anger and determination of a young Jamaican who has

recently moved from the countryside to the city and discovered the myriad

mechanisms both for exploiting people and for hiding that exploitation

behind pious ideological veils. Despite the fact that all three of

these songs have been commodified (packaged and sold for a profit --

on recordings and at concerts) they have also been vehicles for the

international circulation of bottom-up struggle. “Another Brick in

the Wall” has been banned in numerous countries around the world

because of the chord it strikes in the hearts of school children and

students who, again and again, adopted it in their own struggles. One

particularly dramatic example of this occurred in the black township

of Soweto in South Africa where, during a student strike against

apartheid, thousands of black children sang this song while facing

off with the South African police across barricades. A

clip from the film

version of The Wall is now available on You Tube or you can just

listen to the music below.

When we grew up and went to school

There were certain teachers who would

Hurt the children in any way they could

"OOF!" [someone being hit]

By pouring their derision

Upon anything we did

And exposing every weakness

However carefully hidden by the kids

But in the town, it was well known

When they got home at night, their fat and

Psychopathic wives would thrash them

Within inches of their lives.

We don't need no education.

We don't need no thought control.

No dark sarcasm in the classroom.

Teacher leave them kids alone.

Hey, teacher, leave them kids alone!

All in all it's just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

We don't need no education.

We don't need no thought control.

No dark sarcasm in the classroom.

Teacher leave us kids alone.

Hey, teacher, leave us kids alone!

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

Wrong, do it again!

Wrong, do it again!

If you don't eat your meat,

you can't have any pudding!

How can you have any pudding

if you don't eat your meat.

You! Yes, you behind the bikeshed,

stand still laddy!

(ringing)

Pink Floyd, The Wall,

Capitol Records, CDP 724383124329 , 1979.

|

In the case of "The Harder they come" and "You Can Get It if You Really Try"

from the movie/soundtrack The Harder they Come, by

containing some of the most

poignant and passionate moments of reggae music along with a story

line that retells in allegorical and poetic terms the whole history

of primitive accumulation, the film has circulated the struggles of

the West Indian poor far beyond the confines of the Caribbean, bringing

understanding as well as the spirit of resistance to

people all over

the world. (For background see the book by Campbell cited below.)

|

Well they tell me of a pie up in the sky

Waiting for me when I die

But between the day you're born and when you die

They never seem to hear even your cry

CHORUS:

So as sure as the sun will shine

I'm gonna get my share now of what's mine

And then the harder they come

the harder they'll fall, one and all

Ooh the harder they come

the harder they'll fall, one and all

Well the officers are trying to keep me down

Trying to drive me underground

And they think that they have got the battle won

I say forgive them Lord, they know not what they've done

CHORUS

Ooh yeah oh yeah woh yeah ooooh

And I keep on fighting for the things I want

Though I know that when you're dead you can't

But I'd rather be a free man in my grave

Than living as a puppet or a slave

CHORUS

Yeah, the harder they come,

the harder they'll fall one and all

What I say now, what I say now, awww

What I say now, what I say one time

The harder they come

the harder they'll fall one and all

Ooh the harder they come

the harder they'll fall one and all

|

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

But you must try, try and try

Try and try, you'll succeed at last

Persecution you must bear

Win or lose you've got to get your share

Got your mind set on a dream

You can get it, though harder them seem now

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

But you must try, try and try

Try and try, you'll succeed at last

I know it, listen

Rome was not built in a day

Opposition will come your way

But the hotter the battle you see

It's the sweeter the victory, now

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

But you must try, try and try

Try and try, you'll succeed at last

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

You can get it if you really want

But you must try, try and try

Try and try, you'll succeed at last

You can get it if you really want - I know it

You can get it if you really want - though I show it

You can get it if you really want

- so don't give up now

Jimmy Cliff, The Harder They Come,

Mango/Island Records, CD 162539 202-2, 1973.

|

Recommended Further Reading

On the interpretation of everyday popular culture in terms of the

underlying social conflicts of capitalist society, take a look at

some of the following: Henri Lefebvre, Everyday Life in the Modern

World, London: Harper & Row, 1971; S. Cohen and L. Taylor, Escape

Attempts: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Everyday Life,

London: Allen Lane, 1976; S. Hall, “Notes on Deconstructing

the ‘The Popular’“, in R. Samuel (ed) People’s History

and Socialist Theory, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981; B. Waites,

T. Bennett, and G. Martin (eds) Popular Culture: Past and Present,

London: Croom Helm - Open University Press, 1982; Michel de Certeau,

The Practice of Everyday Life, (Volumes I & II), Berkeley: University

of California Press, 1984; F. Jameson, “Postmodernism, of the

Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, New Left Review, No. 146,

July-August 1984; J. Radway, Reading the Romance: Feminism and

the Representation of Women in Popular Culture, Chaptel Hill:

University of North Carolina Press, 1984; John Fiske, Understanding

Popular Culture, Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989; John Fiske, Reading the

Popular, Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989; John Fiske, Power

Plays, Power Works,

New York: Verso, 1993; Edward P. Thompson, Customs in Common: Studies

in Traditional Popular Culture, New York: The New Press, 1993; John

Storey, An Introductory Guide to Cultural Theory and Popular Culture,

Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993..

On working class popular songs and protest music, see: John Greenway,

American Folksongs of Protest, Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania

Press, 1953; Edith Fowke and Joe Glazer (eds) Songs of Work and

Freedom,

Garden City: Doubleday & Co., 1960; Alan Lomax, Hard Hitting Songs for

Hard-hit People, New York: Oak Publications, 1967 (with notes on the

songs by Woody Guthrie); Roy Palmer, The Painful Plow: a portrait of

the agricultural labourer in the 19th Century from folk songs and

ballads and contemporary accounts, London: Cambridge University Press,

1972; Roy Palmer, Poverty Knock: a picture of industrial life in the

19th Century through songs, ballads and contemporary accounts, London:

Cambridge University Press, 1974; Philip S. Foner, American Labor Songs

of the Nineteenth Century, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1975;

Red Notes, A Songbook, London, 1977; Kathy Henderson et al,

My Song is

My Own: 100 Women’s Songs, London: Pluto Press, 1979; Pete Seeger

and Bob Reiser, Carry It On! A History in Song and Picture of the Working

Men and Women of America, Poole: Blandford Press, 1986; Peter Blood (ed),

Rise up Singing: The Group Singing Songbook, Bethleham:

Sing Out, n.d.;

Guy and Candie Carawan (ed) Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil

Rights Movement Through Its Songs, Bethleham: Sing Out, n.d.; Hildred

Roach, Black American Music: Past and Present, Melbourne (Fla.): Krieger,

1992; José Limón, Mexican Ballads, Chicano Poems: History and

Influence in Mexican-American Social Poetry, Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1992. This list only scratches the surface. There

is a vast literature on the subject and a great many collections of

recorded music. Perhaps the best place to start to learn about old

recordings is with the Folkways Catalogue from the Smithsonian Museum

in Washington, D.C., and to learn about new ones, spend some time in

the library with Sing Out! or Dirty Linen magazines.

On contemporary popular music, there is also a vast literature, much

of which is not very useful. You might, however, look at: David

Pichaske, A Generation in Motion: Popular Music and Culture in

the Sixties, New York: Schirmer Books, 1979; Simon Frith, Sound

Effects: Youth, Leisure, and the Politics of Rock n’ Roll,

New York: Pantheon Books, 1981; Horace Campbell, Rasta and

Resistance: From Marcus Garvey to Walter Rodney, Trenton:

Africa World Press, 1987 especially chap. 5: “Rasta, Reggae

and Cultural Resistance”.